|

| February 12, 2019 | Volume 15 Issue 06 |

Designfax weekly eMagazine

Archives

Partners

Manufacturing Center

Product Spotlight

Modern Applications News

Metalworking Ideas For

Today's Job Shops

Tooling and Production

Strategies for large

metalworking plants

50 years ago: Apollo's Lunar Module bridged the technological leap to the Moon

[Countdown Series: 50th anniversary of Apollo 11]

By Bob Granath, NASA's Kennedy Space Center, Florida

On May 25, 1961, President John F. Kennedy challenged America to meet the goal of "landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth."

A first step in that technological leap for NASA was deciding how.

At the time, many NASA managers and engineers believed the most feasible method was "direct ascent," -- a spacecraft launched by an enormous rocket traveling directly to the Moon and landing as one unit. After exploration of the surface, a portion of the lander blasts off, returning to Earth.

President John F. Kennedy speaks in front of an early design for the Apollo lunar module. The large windows were later replaced with smaller, down-facing ones. Seats also were removed, resulting in a design where the astronauts stand. NASA Administrator James Webb, Vice President Lyndon Johnson, Dr. Robert Gilruth, director of NASA's Manned Spacecraft Center (now Johnson Space Center) in Houston, and others participate in the activity on Sept. 12, 1962. [Credits: White House/Cecil Stoughton]

Another approach, called "Earth Orbit Rendezvous," involved the launch of several Saturn 1 rockets. A spacecraft, similar to the direct method, would be assembled in space for the lunar mission.

But a small group of engineers, including Dr. John Houbolt, assistant chief of the Dynamic Loads Division at NASA's Langley Research Center in Virginia, had an idea called "Lunar Orbit Rendezvous." In a 1961 letter to Dr. Robert Seamans, NASA's associate administrator, Houbolt proposed separate vehicles, one to land on the surface while another circled the Moon.

The risky part was the landing craft must rendezvous with the "mother ship" in lunar orbit so the astronauts can return home. At that time, bringing two spacecraft together in space had never been tried. But the landing could require a much smaller spacecraft.

"Rendezvous in lunar orbit is quite simple," Houbolt said. "I would rather bring down 7,000 pounds to the lunar surface than 150,000 pounds."

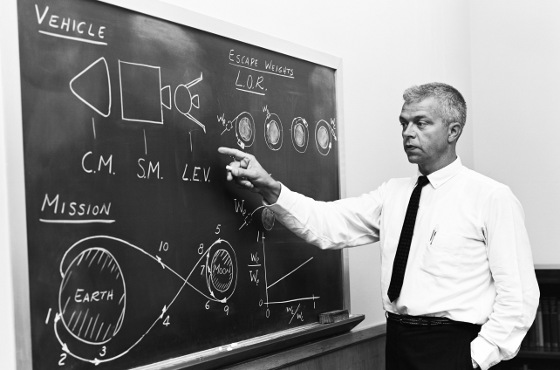

On July 24, 1962, Dr. John Houbolt explains his lunar orbit rendezvous concept for landing on the Moon. His approach called for a separate lander, which saved weight from the "direct ascent" design in which the entire spacecraft landed on the lunar surface. [Credits: NASA]

In his 2005 NASA book, "Project Apollo -- The Tough Decisions," Seamans wrote that he saw great merit in lunar orbit rendezvous.

"Houbolt explained the orbital maneuvers and noted the savings in weight," he said.

While initially a skeptic, Dr. Wernher von Braun, director of NASA's Marshall Spaceflight Center in Huntsville, AL, agreed that the lunar orbit rendezvous approach would simplify reaching Kennedy's goal in a timely manner.

"A drastic separation of these functions into two separate elements is bound to greatly simplify the development of the spacecraft system and result in a very substantial saving of time," he said.

Von Braun led the team that developed the Saturn V rocket to launch the two spacecraft.

Studies and debates continued during the following months.

In the Manned Spacecraft Operations (now the Neil Armstrong Operations and Checkout) Building at NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida, the lunar module for Apollo 10 is being moved for mating with the spacecraft lunar module adapter. Apollo 10 orbited the Moon in May 1969 and served as a "rehearsal" for the first lunar landing. [Credits: NASA]

In a July 11, 1962, news conference, NASA Administrator James Webb announced the decision.

"We have studied the various possibilities for the earliest, safest mission," he said. "We find that by adding one vehicle to those already under development, namely, the lunar excursion vehicle, we have an excellent opportunity to accomplish this mission with a shorter time span, with a savings of money and with equal safety."

Initially dubbed the "lunar excursion module," the name was later changed to simply "lunar module," or LM. According to George Low, manager of the Apollo Spacecraft Program Office, NASA believed the word "excursion" might sound frivolous.

The contract for designing and building the LM was awarded to Grumman Aerospace in November 1962. A year earlier, North American Aviation began work on the "mother ship" called the command/service module.

Initial LM designs included large curved windows and seats and a redundant forward docking port, but redesigns were required to save weight and enhance safety.

The cockpit windows were replaced with smaller triangular versions. A rectangular overhead window was included for use in rendezvous with the command module after leaving the lunar surface.

A forward hatch was designed to make it easier to climb out while wearing the bulky space suits with their backpacks.

Apollo 11 commander Neil Armstrong participates in training on June 19, 1969, in the Apollo lunar module (LM) mission simulator. Simulators for both the LM and command module were located in the Flight Crew Training Building at NASA's Kennedy Space Center. [Credits: NASA]

While there were many key LM systems, nothing was more important than the engines that would allow the spacecraft to land on the Moon and return to the command module.

At the base of the LM was the descent propulsion system. The variable throttle rocket engine allowed astronauts to control the final decent from about 50,000 ft, including hovering as the commander picked out the best spot to land.

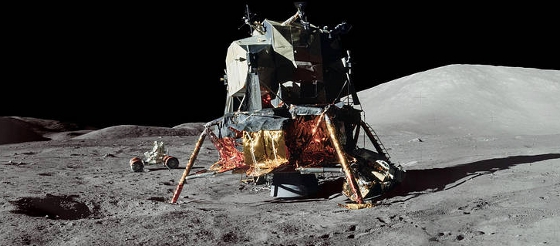

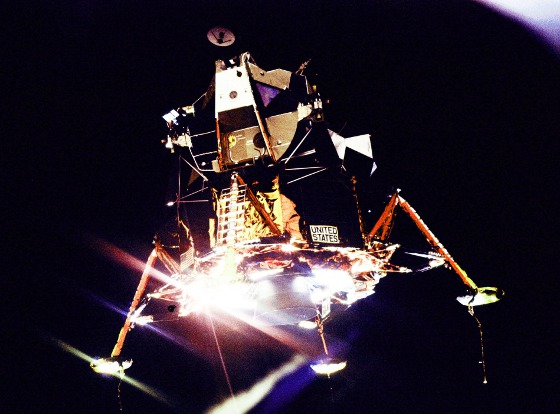

On July 20, 1969, the Sun's glare helps illuminate the Apollo 11 lunar module (LM) with Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin aboard. The LM has just undocked from the command module to prepare for the first landing on the Moon a few hours later. [Credits: NASA/Mike Collins]

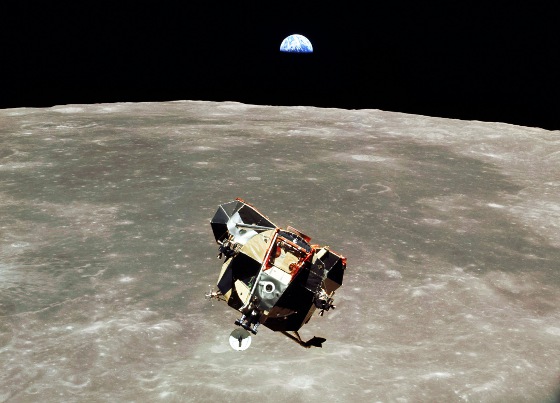

The upper half of the LM served as the ascent stage. It contained the crew cabin with flight controls. The ascent propulsion system engine fired to liftoff from the Moon's surface and into a trajectory for rendezvous with the command module in lunar orbit.

The ascent module also included 16 reaction control system thrusters mounted in groups of four, for maneuvering in both landing and ascent.

The LM's first unpiloted flight test was Apollo 5, launched Jan. 22, 1968. The mission successfully verified operation of the spacecraft's performance, including the descent and ascent propulsion systems. Piloted test flights preceded the first Moon landing attempt. On Apollo 9 in March 1969, the LM was flown in Earth orbit. During Apollo 10 in May 1969, a LM descended to 50,000 ft above the lunar surface.

[Credits: NASA/Mike Collins]

The venerable lunar module showed its versatility serving as a "lifeboat" when the Apollo 13 command/service module was disabled by an oxygen tank explosion en route to the Moon in April 1970. But the LM will be remembered most for its role between July 1969 and December 1972, when six of the spacecraft successfully landed 12 American astronauts on the Moon.

Published February 2019

Rate this article

View our terms of use and privacy policy